You would have to be half dead from egg-toddy to fail to notice that Erdoğan’s talking about the Ladies again. Especially: their privates.

At a recent wedding, Turkey’s president had the following to say:

“One or two (children) is not enough. To make our nation stronger, we need a more dynamic and younger population. We need this to take Turkey above the level of modern civilizations. In this country, they (opponents) have been engaged in the treason of birth control for years and sought to dry up our generation.”

Erdogan’s preoccupation with Turks getting it on, sans capote, is nothing new. In fact, he’s been giving Turkish women more or less subtle fertility advice for a while now, having previously called abortion murder, pleaded Turkish women to have more children, frequently reminding anyone willing to listen that women’s primary role is motherhood and that the jobs of men are unsuitable for women.

According to the latest Demographic Health Survey in Turkey from 2008, around 73 percent of female survey respondents said they used some form of contraceptives (46 percent a “modern method” like the pill, condom, or IUD) and unmet need for contraceptives was around 6 percent. What makes use of contraceptives in Turkey stand out, even among its peers (let’s for a moment assume Tunisia is one, where use of modern methods is 50 percent), is that modern use in Turkey tends to focus more on condoms than pills, 16.9 and 5.3 percent respectively in Turkey, compared to the reverse in Tunisia, 1.1 and 19 percent respectively. As such, even though modern methods of contraceptives have become commonplace in Turkey, on interpretation is that the bias toward condoms reflects men exerting greater control over birth control.

So when Erdogan is saying birth control is treason, he may actually not be talking to women at all but to men.

But getting back to the issue at hand, Turkey’s experienced rapidly declining fertility for years: whereas women used to have four children in 1978, they’re today having around two. There are several reasons why he might be concerned over this. Some may have to do with the fear that the Kurds in Turkey will soon outgrow ethnic Turks, with all sorts of economic and political implications. It could also be an attempt to divert attention from the rather dodgy parliamentary investigation into corruption inside the government. But the reason I want to focus on here, is the economic concerns Erdogan may have over declining fertility.

Some observers have expressed understanding for Erdoğan’s concerns, as made clear in this FT article from last year:

“If you have a young population, the future is yours,” Mr Erdogan has said. “At the moment, thank God, 60 per cent of our population is under 30. But when we look at the increase, if we continue like this, alarm bells are ringing for 2037-40.”

There is more than a grain of truth in his words. UN data show the total fertility rate – the number of children born to each woman during childbearing years – has fallen from 4.3 in 1970-75 to 1.9 in 2010. When the number of children being born falls below 2.1 per woman, there are too few births to keep a population stable.

Yet how damaging is declining fertility really? After all, here in Europe we’ve had rather low fertility levels for a while now.

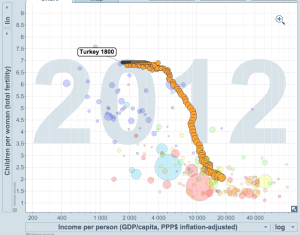

Declining fertility is an integral outcome of economic modernization, often a result of complex process involving , better access to education, higher income levels, urbanization, lower child mortality, and family planning. So, from the start, it’s important to note that complaining that women have too few children is a bit like complaining that Turkey is becoming too rich. The below graph, snatched from Gapminder, shows Turkey’s steep fall in fertility, down to a level largely representative of other countries in the same income group.

Gapminder: http://goo.gl/7Qemb4

The UN Population Division’s projections for future fertility shows the most likely scenario having Turkey converging on a total fertility rate (TFR) at around 1.8.

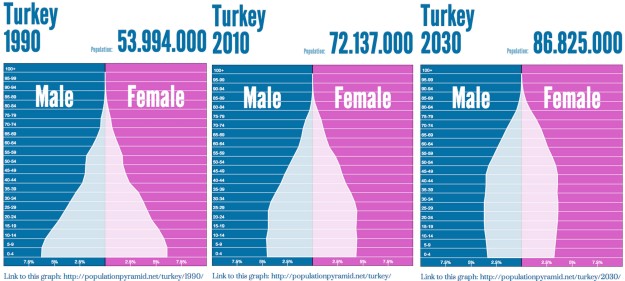

Declining fertility, and its accompanying correlates, used to be – and probably for now is still – good news for Turkey, as it meant the country’s working-age population would keep on increasing as a share of the total population. At the moment, the share of population below 15 is less than 30 percent while the share of the population above 65 is less than 15 percent. These benchmarks happen to be the UN definition for a “demographic window”, when the working-age population group (usually defined as 15-64) is unusually high creating a situation where less resources have to go to “dependents”, allowing a country to grow faster for a period of time.With the UN definition, Turkey has been going thru a demographic window since 2002. Graphically, this means Turkey’s population structure is going from pyramid to what I’d call the “wrapped-chubby-Chistmas-tree-shape”:

According to Bloom et al, one explanation for the phenomenal growth of many East Asian countries in the late 1960s was precisely one such demographic window, or “demographic dividend” (as economist prefer to call it):

“when the baby-boom generation started work, their entry into the workforce changed the ratio of workers to dependents in the population. With the benefits of a good education and a liberalized trade environment, this generation was absorbed into the job market and into gainful employment, thereby increasing the region’s capacity for economic production.”

Given the similar demographic transition occurring now in Turkey, it’s a real opportunity to make the best of the situation.

Of key interest in this literature is the relation between the working-age population and the non-working-age, dependent, population. Sometimes this is measured as the share of the 15-64-year-old population, but even more often it’s characterized as the population of below-15 and above 65 divided by the population between 15 and 64 years of age. This measure is called the age dependency ratio (hereby ADR).

A demographic dividend affects the economy in several ways in terms of behavior, culture (again, via Bloom et al): Increased life spans of children means their parents are more likely to invest in their education, while improved children’s health are likely to increase the the cognitive returns to schooling. With regards to labor supply, there’s both a mechanical effect: more working-age people means more working people; as well as a a gender-effect: as women start to have fewer children, and thus having more time, they should start to enter the labor market more. And as women from smaller families come of working age, they are also more likely to be educated.

And Turkey needs more higher-skilled workers, as made clear in a recent Conference Board Report noting that Turkey’s productivity growth has been declining, that it’s becoming more labor-intense, and that its “struggling with its transition from a low-cost producing economy to a higher position in the value chain and raising its efficiency through productivity-enhancing investments in labor skills, technology, and innovation.”

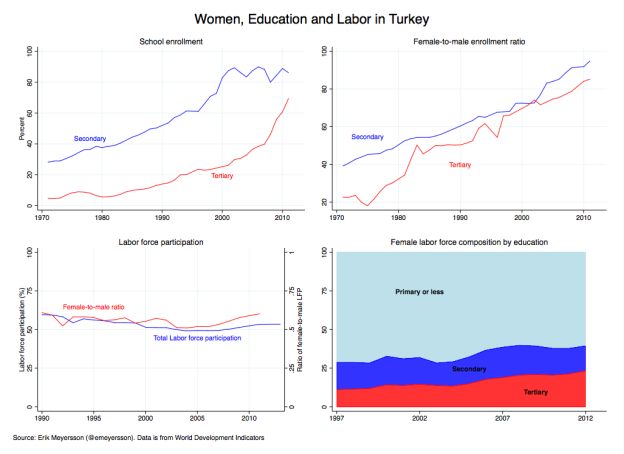

If you were looking for large group of rather well-educated potential workers in Turkey,a first step would be to turn to women. After all, women are already having fewer kids, and as the below graph shows, education levels in both secondary and tertiary education have increased, in absolute (upper left figure) as well as in terms of gender equality (upper right figure):

However, as the lower figures show, labor force participation (hereby, LPR) among women (the red line marking the female-to-male ratio of LPF in the lower left figure) has remained mostly constant since 1990. (Recent years have seen a small pickup in this ratio but that could as well have been a reversal to the level before the crisis of 2001). And even though the composition of the female labor force in terms of educational attainment (lower right) shows a non-trivial increase in the share of university-educated women in the labor force, these still remain a significant minority. Most women in the labor force are those with primary (or less) education (and although it’s not shown here, most are in the agricultural sector).

Consequently, for Turkey to harness its demographic window, it’s going to have to generate higher-skilled, more productive, workers. And given the absence of women in the workforce, a logical first step would be making sure women gain access to the labor force. It is therefore surprising that, instead of doing his utmost to tell everyone wanting to listen that women in the labor force is the way to go, Erdogan instead says their main role is motherhood (not working careers) and that they should have more children.

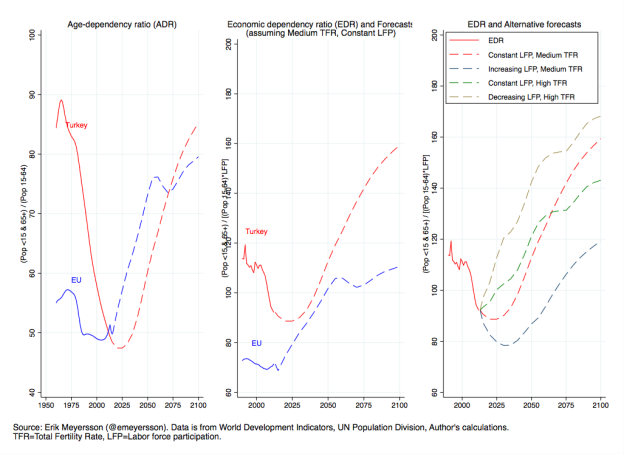

To illustrate the problem with this mindset, in the below lef-hand graph I plot the the age-dependency ratio (ADR), which again denotes the number of a country’s population that are either below 15 years of age or above 65 years of age, divided by the population of 15-64-year-olds, to measure the ratio of those typically not in the labor force against those typically in the labor force.

The left-hand graph shows Turkey’s ADR, in red, rapidly decreasing (as the working-age population increases relative to the dependents) as a consequence of declining fertility reducing the share of below 15-year-olds. The dashed red line represents the UN’s projections for Turkey’s future ADR in the baseline case it refers to as “Medium fertility” (see here for details on the UN’s forecasts, and here for the data). Turkey’s ADR is expected to bottom out just before 2025, and thereafter to start rising as the country’s population ages. By 2050, Turkey will have roughly the same ADR as in 1990, but then it will be the old who are the dependents, not the young. At this time, if Turkey’s hasn’t been able to increase the productivity of these fewer workers, demographics will put downward pressure on long-term growth.

I’ve also plotted the corresponding ADR and forecast for the EU as a comparison (actually it’s EU for the historical ADR and Europe for the forecasts as UN only produces aggregate forecasts for Europe, not for EU), which shows an initially much lower level of the ADR, but a correspondingly faster increase than Turkey going forward. This is because the EU has less young people to start with and is expected to age more rapidly. On the other hand, the labor productivity growth is higher in the EU than in Turkey, which again signifies Turkey’s need for a more productive work force.

The ADR is a fair measure of “economic dependency” when the labor force participation is 100 percent, but as this rarely the case, it’s of interest to look at a more precise measure of this. For this purpose I divide the ADR by the labor force participation rate (LPR) for the 15-64 age group, to measure the economic dependency ratio (EDR), i.e the number of old and young relative to the actual working population in the 15-64 age group.

Doing this results in a somewhat different picture. First of all, the levels of the EDR are (unsurprisingly) higher for both Turkey and the EU, but more interestingly, Turkey’s EDR never crosses the EU’s. In other words, Turkey’s lower LPR results in a much steeper rise while the EU, although it is already older from the onset, is helped along by its much higher LPR (71% in 2013 compared to Turkey’s 53%). So not only does Turkey have to increase the productivity growth of its existing labor force, it also desperately needs to expand it (without losing in productivity).

So, what should Turkey do with regards to women? Get women to have more babies or get them (especially the higher-educated ones) into the labor force? To get a sense of how these two different strategies could affect the economic dependency ratio, the last figure shows three alternative scenarios other than the previously discussed forecast for Turkey.

Scenario 1: Women enter the labor force incrementally, no change in fertility trajectory

The first scenario (the dashed blue line) alters the UN forecast in one simple way: it assumes that Turkey’s LPR grows at 2 percentage points every 5 years up until the EU average of 71% (and slightly lower than Turkey’s male LPR at 76 percent) and then remains constant. This combines a rather optimistic assessment of the final LRP level with a more modest path towards this goal. Representing the blue line in the graph, it continues to fall below the standard (red line) forecast, crosses the EU’s line and stays below it until around 2075. Under this scenario, Turkey’s EDR doesn’t reverse back to its 1990 level until close to the end-date 2100. Basically, increasing the LPR buys Turkey more time before the reversal.

Scenario 2: Women’s labor force participation remains constant, high fertility trajectory

The second forecast alters the standard one in that it assumes what the UN refers to as “High fertility”, meaning one half more children than in the “Medium” case. In this case, the green line in the figure, the EDR climbs initially quicker than the standard case, at least initially, and will be back at 1990 levels in 2040. The faster increase under this scheme is likely the result of not just a growing old population but also that the number of young people decrease less rapidly. Point is, increasing fertility in this scenario under the UN assumptions hastens the reversal to increased economic dependency.

Yet, if we were to assume higher fertility, perhaps as Erdoğan gets some of his will through, would it not also be correct to assume that the female LPR will also decrease? (Remember, according to Erdogan, women’s most important role is motherhood!).

Scenario 3: Women incrementally leave the labor market, high fertility trajectory

In the final scenario, I take the same assumptions on (high) fertility as before but allow the LPR to decrease at 2 percent level every five years until it hits 45 percent and then remains constant. This end-estimate of LPR is based on the assumption that at this point, half of all women will have left the labor market.

This scenario, the brown line, is by far the most adverse for Turkey. Now that the LPR is declining as women switch from work careers to motherhood-only careers, the EDR increase so rapidly that it will have reversed back to its 1990 level already by 2025.

The point of this exercise is not to claim that the UN forecasts or my adjustments, are based on assumptions that shouldn’t be up for discussion and critique. Nor am I claiming that a low ADR or EDR equals higher economic growth. Instead, the point here is that, to the extent that “dependency” is an issue for Turkey’s future economic progress, it’s quite unclear how inducing Turkey’s women to have more children, likely at the expense of lowering their already abysmally low labor force participation, will improve the its economic prospects.

In other words, whereas Erdoğan’s comments are not only problematic from a strictly women’s rights perspective, they also appear to be counterproductive from a growth standpoint. Turkey’s real challenge during its demographic window is not to get as big a population as possible but to increase the productivity of the population it already has. And if the Turkish government is so concerned about future economic dependency, the absence of women in the labor force marks a great competence reserve that could and should be put to better use.

Furthermore, if Erdogan is so concerned about ethnic Turks declining fertility relative to ethnic Kurds, he’d probably be much more successful making sure economic development reaches Kurdish areas too, so they can go through the same fertility decline that the non-Kurdish areas have, rather than trying to reverse decades of forces way more powerful than his policies (or speeches) are ever going to be.

A large part of Turkey’s economic progress up until now has been a result of declining fertility, facilitated through family planning. To criticize the use of birth control in Turkey is like criticizing it for becoming a modern country, both socially and economically. Attempts to reverse fertility trends are likely to prove futile at best, and outright dangerous at worst.

Women hold the key to Turkey’s future development. That key should go to an office, not a chastity belt.